-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 0

Breakout Tutorial

This is a rough work in progress at the moment that is neither complete nor final, but as it is being updated I will keep it visible for anyone to comment on if they feel I can be going in a better direction or just have tips/opinions. (One key missing thing is that pictures will eventually be added of some steps to make them clearer and the block adding process easier to understand)

Table of Contents

- Getting Started / Making the paddle

- Explaining Sprites

- The main loop and drawing objects

- Getting user input and using messages

- Adding the ball

- Using bounce

- Using direction and speed

- Making the ball bounce off the paddle

- Collision detection

- Adding the blocks

- Using arrays

- Adding points and lives

- Custom variables

- Adding sounds

- Sound blocks

- Frequency by color

In any programming language it’s key to break down problems into their basic components. In Waterbear this is even more true, as those basic components will translate into the blocks that you will join together to form your program. In this case we will be building up the classic game “Breakout!”, and the finished program is available within the examples on the Waterbear website.

Breakout has a lot of bells and whistles, but if we strip out the lives, points, music, and even the blocks we’re left with a simple paddle and bouncing ball. We can even start with just a paddle. The paddle will need to be a rectangle drawn on the screen and controlled by the left and right arrows, and not allowed to leave the edges of the screen. In Waterbear we have several sections related to drawing shapes on the screen: Sprites, Images, Rects, and Shapes. Images, Rects, and Shapes all deal with static images which are drawn at a certain point and are intended to largely stay there. Sprites however possess extra traits of direction, movement, and even collision. For a game like Breakout, this is the section we will use for the majority of our objects.

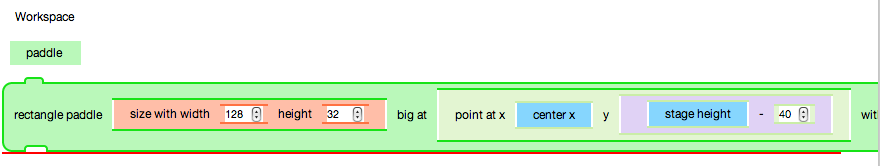

To create our paddle we will drag in our sprite creation block, “rectangle sprite ___ big at ___ with color _____”.

When it’s dragged in Waterbear will automatically assign it a name, and add it to the collection of global objects at the top of the playground, in the area called the Workspace. The automatic name is just the type of object and unique number, but we can rename it to something more meaningful by double clicking on the workspace block and changing the name, which will automatically update the references.

The rectangle sprite has three variables which need to have initial values, namely the size, location, and colour. These go in the holes in the block, which are called sockets. When you dragged in the block they were automatically filled with default values. The size is another object which contains the width and height, and we will simply change these values to what our paddle needs. Points are also objects, and here we do want to make a bigger change, because the paddle should not be at a random point. We will grab this point block and pull it out of our sprite block, and delete it by dropping it off the left of the screen. Now that we have an empty socket, we go into the Points menu and grab the block that will let us specify a point in x and y values.

Notice now that blocks tend to have a few different basic types demonstrated by appearance. Some blocks have the bump on top and whole on the bottom which lets them link with other similar blocks. These are called step blocks, and take actions. They link together because our program will be a series of actions that the program moves through. Some blocks however, like centre x, do not have these bumps. This is to show that they cannot stand alone as steps, but are rather variables. They return and signify some value, and are placed in the sockets of other blocks to add information to steps which need it. There is one third kind of block which we have not yet encountered but will eventually for the backbone of our program, which is the control block, found within the Control menu. These blocks are smooth and curved on the top, but have a space for a step block to connect underneath them. When you drag them into the playground they encompass the step blocks added within them, and this lets these steps be dependent on the control block. This will be the case when we want blocks to only happen if some other condition is true, or if we want to repeat the steps some number of times without having to drag them out over and over again.

Now let’s go back to our program. We’ve gotten our x, but what is the y? We want the paddle to be near the bottom of the screen. We could use a constant value, but then we’d have to make some assumption regarding the vertical size of the screen and it’s better to let Waterbear figure that out for us in case it changes. If we look through the Sensing menu we can see that the stage height is close to what we want, but since the location to draw a sprite is from the top left corner using that as our y value would draw our paddle off the bottom. We need to subtract our paddle height plus a little wiggle room. To do this we need to look into the Math menu. Math contains blocks for most mathematical operations we could need to compute, and contain sockets which let us drop in variables to apply the math to. So we drag in a subtraction block, the stage height in the first socket, and a little more than the height in the second socket.

Our final initial variable is the colour, which we could leave as random but it’d be nice to have some consistency so let’s drag that out and discard it. This leaves a little square of colour, which when we click on lets us select a colour. (Does this depend on OS? Work on Mobile?) Now we are finished defining our block, and need to draw it. For a sprite this is simple, there is a draw block which takes as a socket a sprite to draw. This is where our workspace comes in, because we will grab our paddle variable block and drag it down, which creates a copy or reference which we can place in as many blocks as we want. Once this is placed in the draw sprite block we have enough basic steps that we can run the program.

Now that we’ve got the paddle drawing we need to move it. To do this we will need to be updating the x and y values of the paddle and redrawing it when it changes. Later on there will be other objects which need to move and draw, as well as game logic that has to be figured out, so we’re going to take this chance to create the main loop of our game that will be responsible for updating all of these things. We’re also going to save ourselves some trouble later by keeping in mind that we won’t want our game to last forever, it should end when we’re out of lives. So looking under the Control menu, the block we need is “repeat __ times a second until ___”. The first socket is used to control how fast the loop runs. The second is the condition while causes the game to exit, and for now we’ll leave make it “false” to make our loop run forever.

Now we can drag our draw sprite block into this main loop. If we run it again things don’t look any different, but we can add a new block which will be useful and also make the change more apparent. Right now we’re just drawing our pixels on the default white background, but let’s say we want to make it black instead. Inside the Sprite group there is a “clear stage to color ___” block. Let’s drag that into our main loop, before our “draw sprite paddle” block. The one socket for this block is a color, and it defaults to using the color creation block which takes in red/blue/green/alpha values. This will do for now, since red 0, blue 0, green 0 is black. Run the program to see how it looks. You’ll notice that there’s a nice fade in effect, which is due to the alpha being 0.1 at default, which means slightly transparent. It takes a few cycles for the transparent black to layer up to a solid color, resulting in the fade. If you change the alpha to 1.0, you’ll see that it just goes straight to solid black. Note that we placed the stage clearing before our paddle drawing. The stage clearing will always have to be first because the drawing happens in the order of our blocks, and having the stage clear at the end would have it draw over top of all of our other sprites, making everything black.

Now that we’re drawing every frame we can update the position of the paddle to see it move. We will need to detect two different inputs, left and right arrow, and react accordingly. This is a chance to introduce another idea in programming, that of functions. Sometimes we have a complicated set of steps which we’ll use over and over. Instead of having to keep dragging in those blocks, we’re going to give that grouping a name and just refer to that name instead, which will cause that group of blocks to run. In Waterbear this is handled with messages, under the Control menu. There are two necessary blocks, “broadcast ___ message” and “when I receive ___ message”. The broadcast is what will be in our main program and the socket will be filled with the name of whatever function we want to call. The receive is a container block, and will have all of the steps we want to be taken when a message with that particular function name is sent out. We are going to put user input in a function, so that we can keep our main loop cleaner. So first we will define what our function does by dragging in a “when I receive ___ message” block underneath our main loop, and we’ll change the name from “ack” to “userInput”.

User input is covered in the Sensing menu, and keyboard input is done via the “key ___ pressed?” block. This block will return true what the selected key is pressed, and to make it so that we can dictate what to do when this is true we’ll use an if statement, which is done via the “If ___” block in Control. An if statement simply says “if ___ is true, take the following steps”, and we drag in any block which will return true/false to get our condition. So we drag an “if ___” block into our userInput function container, and then drag the “key ____ pressed?” block into the socket of the if block. We’ll use the drag down of the key pressed block to select “right” for the right arrow key, and now we’re ready to move the paddle. We know we want to move by some fixed amount in the x direction, so looking through the Sprite menu we can see that there is a “move ___ by x __ y __” block which will let us do what we need. Drag that into the if container, fill the first socket with the reference to the paddle like we did with the drawing block, and then in the second socket put in how many pixels you want the paddle to move by. This will dictate the ‘speed’ of the paddle. We’ll start with just 1.

Now we need to do the same thing, but for the left arrow. Make an if block like with the right key, but when you are putting in the x movement for the paddle you have to make it negative. The top left corner of the screen is 0, 0 so in the x direction positive is right and negative is left, and for the y direction up is negative and down is positive. Once that’s done we just need to broadcast a userInput message in our main loop with the “broadcast ____ message” block (before the draw block, since we want our paddle drawn in the updated position), then we can test it out!

Now we would like to add our second major sprite, the ball. The basic functionality of our ball is very simple, we want it to be constantly moving around the screen and bouncing off of any other physical object it hits, including the walls. Since this is a fairly common idea, Waterbear has made the “bounce ___” block to simplify it for us. What the bounce block does it check if a moving sprite has reached any edge of the screen, and if so reverses its direction so that it bounces appropriately.

So, in the same manner as the paddle we create a new ball sprite. We have the creation block underneath the paddle’s, the bounce block underneath the broadcast userInput block, and finally the draw block under the paddle’s draw. But we also need to add some new blocks, since the ball is moving outside of user control. This is achieved by a few properties: Speed Direction Move block The speed and direction dictate where the block will go, and the move block must be called to make the sprite actually move along this path. What the move block does is basically like what we did with the user input, it uses the speed and direction to calculate the changes to the x and y of the sprite and adds or subtracts them. We can set the speed right after we create the ball using the “set sprite ___ speed ___” block. The direction is a little more complicated in that direction is split into two type: turn and steer. This can be considered to be like steer is the direction the sprite is moving, but turn is the direction the sprite is facing. We only have to worry about steer because we don’t really care about the rotation of where the sprites are facing since it’s all just rectangles, but you can play with it if you’d like. If you prefer to have the square ball change facing when it changes direction you can do it easily by using the “autosteer sprite ___ ___” block and setting it to true. Autosteer makes it so that changing the facing of the sprite with “turn” automatically changes the steer direction to match. So we would first set autosteer to true, and then instead of setting the steer would set the turn, because it would then automatically set the steer.

But with that aside, we add the “turn sprite to ___ degrees” block underneath the speed block, and to get a random direction we’ll go into Math to find the “pick random __ to __” block and use 0 and 360 as our upper and lower bounds respectively. Now our ball has a direction and speed for movement and we just need to add the “move ___” block to our main loop. With that done we can run it and observe how bounce works, as well as play with the speed.

Now that our ball is bouncing around the screen, we need to add interaction with the paddle. This involves a few steps: Detecting when the ball is intersecting with the paddle (collision detection) Figuring out how the direction of the ball should be changed to bounce properly

Collision detection at its heart involves comparing the x and y values of the two sprites to figure out in what way they are colliding. Luckily Waterbear simplifies this as well with the “sprite --- collides with sprite ---” block within Sprite. Notice that it is red instead of green, which indicates that even though we group it with the Sprite blocks it is really a Boolean block as it returns a boolean values (true or false). Since handling collisions is going to take several blocks and be done every cycle of our loop, we’re going to put it in a function like we did with userInput. So we make a function which we label handleInput, and within it add an “if” block with the boolean in the socket, and the paddle and ball sprites in the two sockets of that boolean. Now we have to figure out how to make the ball bounce. Waterbear has a block to simplify this as well, “bounce sprite ___ off of sprite __”. We’ll drag it into our if block and say that sprite ball should bounce off of sprite paddle. There is however one extra detail, in that later we will care about whether the ball is below the top of the paddle. But since the ball has a speed of more than one it can actually be several pixels inside the paddle when our collision detection is called. So we want to adjust the ball to place it right at the top of the paddle instead of inside it, which will also help make sure the ball never gets stuck inside the paddle. To do this we use the “move ___ by x _ y” block with the sprite of ball, x of 0, and y of sprite (paddle) top - spite (ball) bottom, i.e we’re subtracting however many pixels inside the paddle the ball is. With this done we can run the program and test our bouncing ball.

Now that we can bounce our block and move our paddle, we need something to actually direct our blocks at. In Breakout this is several layers of blocks along the top of the screen that are destroyed when the ball bounces off of them. To take advantage of the easy collision detection we are going to want these blocks to be Sprites, but we have a problem now. Each sprite we created so far has needed a construction block with several parameters, and to handle 10, 20, or 40 blocks would be time consuming and take up a lot of space. To avoid that, we’re going to use something called an array.

An array is like a kind of special list, and is handled under the Array menu. An array can hold any type of object, but all objects within a single array must be of the same type. So we could have an array of sprites and an array of numbers, but we couldn’t mix numbers and sprites in one array. To start with we just need to make the basic array, which will be empty, using the “new array” block, which will go with the rest of our construction blocks. We will also rename the array to “blocks” to make the code clearer. Now we need to add the sprites to our array, but we do still need to actually create each sprite using a construction block. The information for each block doesn’t change very much, so we can actually use a repeat control block like we did with our main loop to create these blocks in a loop instead of having 40 construction blocks in a row. So we will drag in the “repeat ___” block and change the number to 40. Notice that like our repeat per second block it has given us a count variable, which tells us how many times we’ve repeated. This time we’ll be using this, since we need the location of each destroyable block to change. So first we pull the usual Sprite construction block into the repeat. We can set the size and colour to whatever we want. The tricky part is the position. It can take some tweaking to decide how exactly you want to space your blocks, but the basic idea is:

- Figure out how many rows/columns you want. We will go with 4 rows, 10 columns.

- For the x value, you need to take the desired width of your block plus a little spacing (say, 5 pixels), and multiply that by whatever column the current block is in. To figure this out, you take the counter modulus [number of columns].

- For the y value, you must take the height of your block plus spacing and multiply that by whichever row you are in. To calculate this we want to divide the counter by 10, but since we don’t want fractions we need to round down, which is called the “floor” function in Waterbear.

Once you have the math set up feel free to play with the size of the blocks and spacing until you get an appearance you’re happy with. A more advanced version would take into account the width of the stage, but we are going to stick with this version for now.

Now that we’ve defined what a given block is, we need to add it to our blocks array. Adding to an array is called ‘appending’ so we use the “array ___” append __” block. We get the sprite reference to use from the top of the repeat loop, the same that we did with the count. Why is this sprite reference there instead of at the top with the others? When you define a new object like a sprite within a control block like repeat that object is a ‘local’ object, which means that it is only usable within that control. If you want to use it throughout the program you need to either create it outside the control block and edit it, or add it to some object outside the control block like we did with the array. With those two blocks in place, our repeat control block will go through and generate all 40 block sprites for us. But they aren’t very useful until we draw them. We could use a repeat block again, but the Array menu actually gives us a special block for when we want to do something to every object in an array, the “for each” block. It gives us an item reference which we can then do something with, as well as an index which is a number representing which position that item is in the array, like a counter. So we just add a draw sprite block, drag in the item, and it will draw all of the blocks in our array.

We have all of the main components drawn now, but we still need the ball and blocks to collide. This involves a lot of complicated math, which will hopefully soon be unnecessary due to the “sprite ___ bounce off sprite ____” block. Assuming that we did have such a block, it would be as simple as adding the collision check to the for each block we just added for drawing. When a block was hit we would call the bounce off block, and also use the “array ___ remove item ___” block, which is a little more complicated in that you’ll notice it’s not a step block. This is because the block returns the removed item as a variable. In some cases this would be useful, but we don’t need to use it, so we’ll just put it in a variable that we won’t use again. Now we can destroy blocks, and the basics mechanics of Breakout are complete.

Our game has reached a state of being playable, but it’s not very fun when there’s no progress or difficulty. We need destroying blocks to give you points. Points will be a variable which we’ll define at the start of the program, using the “variable ___” block. Change the name to “points”, and set the initial value to 0. Now we need only increment the score by one point whenever a block is destroyed, which we can do in our collision detection “if” block, using the “increment ___ by ___” block. It doesn’t do us much good to have points if we can’t see them though, so we’ll need to write the text to the screen. This is done through the “Text” menu. The text will be black however, so unless we have a coloured background we need to draw a background for the text. Since we don’t need all of the additional features of the Sprite class we can use the simpler Shape and Rect menus. Shapes gives us the “fill rect ___ with color ___” block, and then from Rect we can define “rect at x __ y ___ with width __ height ____”. The bottom left is a good place for a score, so we use x = 0 and y = stage height - 20. The width is 100 and height 20, and we’ll use the color white. Now for the text we use “fill text ___ x __ y __”. For the text we want to say “Score: [points]” and to combine those two parts we use the “concatenate __ with ___” block from the Strings menu. The x value for text represents the centre of the text as opposed to the leftmost side as with sprites, so we’ll use 50 as our value, and then for y subtract 10 from the stage height. When you run the program you’ll notice that the text is very small by default, so to make it more usable we’ll add one more block. “font __ __ ___” lets us set various font values, including the size, so we’ll increase that to 14. We now have a visible score!

The next step is to add lives, so that we can have a losing condition. This will be another variables, which we’ll create like we did with the points. A life is lost when the paddle misses the ball, which means that the y value of the ball moves past that of the paddle. To keep our main loop tidy we can consider this like a type of collision, so within our collision function we add a new “if” block which checks if the bottom of the ball is greater than the top of the paddle. Within this block we increment lives by -1, and then ‘reset’ the ball by moving it back to the centre of the screen and setting the steer direction the same way we did in the beginning. Now we need only display the lives along with the score, using further concatenation. We have to make some adjustments to our x and y location, as well as the size of the background rectangle, but then we can test a function Breakout game. There is only one remaining flaw, namely that reaching 0 lives has no effect. This is when we will go back to that “until” part of our main loop, and replace the false with a check from the Math menu that lives = 0. Now we have a real game!

The icing on the cake is to add sounds for when the ball collides with the other objects in the game. To do this we use the Music menu. In Waterbear you make sound using Voices, which are objects like Sprites. A voice has a certain frequency in Hertz, a volume, and can be turned on and off or played for a specific duration. To start we will create a voice for our sounds at the top of the program, and set its volume to 1. Let’s first look at when the ball collides with the paddle. Going back to our checkCollisions message we had the if block for collision between the paddle in sprite. In the control block we’re going to add the block “play voice ___ for __ seconds”, and select 0.2 seconds so that it is a short beep. Run the program and you should be able to hear the noise when the ball hits the paddle. Now we just do the same thing in our if control block for collision between the ball and a block, and our game has music.

As an extra touch to play further with the sound blocks, we can make the frequency of the sound for the block collision depend on the colour of the block. We can’t access the color of a sprite, so we will add a new array at the beginning of the program called blockColors. Then in the repeat block where we create the block array we’ll make a few changes. We can’t just use random color since we need to know what the color values are, but we do still want the color to be random. So we will create three variables within the repeat block, called red, blue, and green. We will set these blocks to be a random number from 0 to 255 using the Math “pick random __ to ___” block. Then instead of using random color when creating the sprite we will use a “color with red __ green ___ blue ___” block and drag in the appropriate variables. Our frequency is going to need to be a single number, so we’ll use the sum of these three color values. That is therefore what the blockColors array will store, so we add a block to append the sum of these variables to the blockColors array. Now that we have the numbers we need available we go back to our collision detection for blocks and ball and before the play voice block we add a “set voice ___ tone __ Hz” block, where the tone is “array __ item __” with the blockColors array and index provided by the encompassing “array __ for each” block. If you run now you should hear that the tone varies between blocks, though it does not go back to the initial tone when hitting the paddle so we must also go to the paddle collision and add a block to set the voice’s tone to 400 Hz before playing.