+

+

+### Understanding charts

+

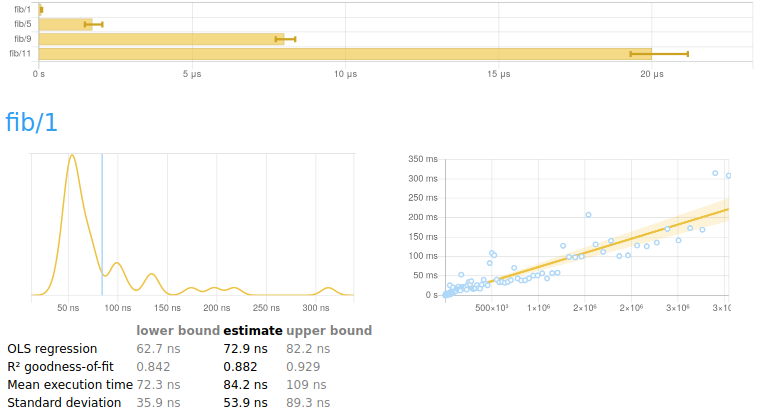

+A report begins with a summary of all the numbers measured.

+Underneath is a breakdown of every benchmark, each with two charts and

+some explanation.

+

+The chart on the left is a

+[kernel density estimate](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kernel_density_estimation)

+(also known as a KDE) of time measurements. This graphs the

+*probability* of any given time measurement occurring. A spike

+indicates that a measurement of a particular time occurred; its height

+indicates how often that measurement was repeated.

+

+> [!NOTE]

+> **Why not use a histogram?**

+>

+> A more popular alternative to the KDE for this kind of display is the

+> [histogram](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histogram). Why do we use a

+> KDE instead? In order to get good information out of a histogram, you

+> have to

+> [choose a suitable bin size](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histogram#Number_of_bins_and_width).

+> This is a fiddly manual task. In contrast, a KDE is likely to be

+> informative immediately, with no configuration required.

+

+The chart on the right contains the raw measurements from which the

+kernel density estimate was built. The $x$ axis indicates the number

+of loop iterations, while the $y$ axis shows measured execution time

+for the given number of iterations. The line “behind” the values is a

+linear regression generated from this data. Ideally, all measurements

+will be on (or very near) this line.

+

+

+### Understanding the data under a chart

+

+Underneath the chart for each benchmark is a small table of

+information that looks like this.

+

+| | lower bound | estimate | upper bound |

+|----------------------|-------------|------------|-------------|

+| OLS regression | 31.0 ms | 37.4 ms | 42.9 ms |

+| R² goodness-of-fit | 0.887 | 0.942 | 0.994 |

+| Mean execution time | 34.8 ms | 37.0 ms | 43.1 ms |

+| Standard deviation | 2.11 ms | 6.49 ms | 11.0 ms |

+

+The second row is the result of a linear regression run on the measurements displayed in the right-hand chart.

+

+* “**OLS regression**” estimates the time needed for a single

+ execution of the activity being benchmarked, using an

+ [ordinary least-squares regression model](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ordinary_least_squares).

+ This number should be similar to the “mean execution time” row a

+ couple of rows beneath. The OLS estimate is usually more accurate

+ than the mean, as it more effectively eliminates measurement

+ overhead and other constant factors.

+

+* “**R² goodness-of-fit**” is a measure of how accurately the linear

+ regression model fits the observed measurements. If the measurements

+ are not too noisy, R² should lie between 0.99 and 1, indicating an

+ excellent fit. If the number is below 0.99, something is confounding

+ the accuracy of the linear model. A value below 0.9 is outright

+ worrisome.

+

+* “**Mean execution time**” and “**Standard deviation**” are

+ statistics calculated (more or less) from execution time divided by

+ number of iterations.

+

+On either side of the main column of values are greyed-out lower and

+upper bounds. These measure the *accuracy* of the main estimate using

+a statistical technique called

+[*bootstrapping*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bootstrapping_(statistics)). This

+tells us that when randomly resampling the data, 95% of estimates fell

+within between the lower and upper bounds. When the main estimate is

+of good quality, the lower and upper bounds will be close to its

+value.

+

+

+## Reading command line output

+

+Before you look at HTML reports, you'll probably start by inspecting

+the report that criterion prints in your terminal window.

+

+```

+benchmarking ByteString/HashMap/random

+time 4.046 ms (4.020 ms .. 4.072 ms)

+ 1.000 R² (1.000 R² .. 1.000 R²)

+mean 4.017 ms (4.010 ms .. 4.027 ms)

+std dev 27.12 μs (20.45 μs .. 38.17 μs)

+```

+

+The first column is a name; the second is an estimate. The third and

+fourth, in parentheses, are the 95% lower and upper bounds on the

+estimate.

+

+* `time` corresponds to the “OLS regression” field in the HTML table

+ above.

+

+* `R²` is the goodness-of-fit metric for `time`.

+

+* `mean` and `std dev` have the same meanings as “Mean execution time”

+ and “Standard deviation” in the HTML table.

+

+

+## How to write a benchmark suite

+

+A criterion benchmark suite consists of a series of

+[`Benchmark`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#t:Benchmark)

+values.

+

+```haskell

+main = defaultMain [

+ bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

+ , bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

+ , bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

+ , bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

+ ]

+ ]

+```

+

+

+We group related benchmarks together using the

+[`bgroup`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:bgroup)

+function. Its first argument is a name for the group of benchmarks.

+

+```haskell

+bgroup :: String -> [Benchmark] -> Benchmark

+```

+

+All the magic happens with the

+[`bench`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:bench)

+function. The first argument to `bench` is a name that describes the

+activity we're benchmarking.

+

+```haskell

+bench :: String -> Benchmarkable -> Benchmark

+bench = Benchmark

+```

+

+The

+[`Benchmarkable`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#t:Benchmarkable)

+type is a container for code that can be benchmarked.

+

+By default, criterion allows two kinds of code to be benchmarked.

+

+* Any `IO` action can be benchmarked directly.

+

+* With a little trickery, we can benchmark pure functions.

+

+

+### Benchmarking an `IO` action

+

+This function shows how we can benchmark an `IO` action.

+

+```haskell

+import Criterion.Main

+

+main = defaultMain [

+ bench "readFile" $ nfIO (readFile "GoodReadFile.hs")

+ ]

+```

+([examples/GoodReadFile.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/GoodReadFile.hs))

+

+We use

+[`nfIO`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:nfIO)

+to specify that after we run the `IO` action, its result must be

+evaluated to normal form, i.e. so that

+all of its internal constructors are fully evaluated, and it contains

+no thunks.

+

+```haskell

+nfIO :: NFData a => IO a -> Benchmarkable

+```

+

+Rules of thumb for when to use `nfIO`:

+

+* Any time that lazy I/O is involved, use `nfIO` to avoid resource

+ leaks.

+

+* If you're not sure how much evaluation will have been performed on

+ the result of an action, use `nfIO` to be certain that it's fully

+ evaluated.

+

+

+### `IO` and `seq`

+

+In addition to `nfIO`, criterion provides a

+[`whnfIO`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:whnfIO)

+function that evaluates the result of an action only deep enough for

+the outermost constructor to be known (using `seq`). This is known as

+**weak head normal form** (WHNF).

+

+```haskell

+whnfIO :: IO a -> Benchmarkable

+```

+

+This function is useful if your `IO` action returns a simple value

+like an `Int`, or something more complex like a

+[`Map`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/containers/docs/Data-Map-Lazy.html#t:Map)

+where evaluating the outermost constructor will do “enough work”.

+

+

+## Be careful with lazy I/O!

+

+Experienced Haskell programmers don't use lazy I/O very often, and

+here's an example of why: if you try to run the benchmark below, it

+will probably *crash*.

+

+```haskell

+import Criterion.Main

+

+main = defaultMain [

+ bench "whnfIO readFile" $ whnfIO (readFile "BadReadFile.hs")

+ ]

+```

+([examples/BadReadFile.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/BadReadFile.hs))

+

+The reason for the crash is that `readFile` reads the contents of a

+file lazily: it can't close the file handle until whoever opened the

+file reads the whole thing. Since `whnfIO` only evaluates the very

+first constructor after the file is opened, the benchmarking loop

+causes a large number of open files to accumulate, until the

+inevitable occurs:

+

+```shellsession

+$ ./BadReadFile

+benchmarking whnfIO readFile

+openFile: resource exhausted (Too many open files)

+```

+

+

+## Beware “pretend” I/O!

+

+GHC is an aggressive compiler. If you have an `IO` action that

+doesn't really interact with the outside world, *and* it has just the

+right structure, GHC may notice that a substantial amount of its

+computation can be memoised via “let-floating”.

+

+There exists a

+[somewhat contrived example](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/ConduitVsPipes.hs)

+of this problem, where the first two benchmarks run between 40 and

+40,000 times faster than they “should”.

+

+As always, if you see numbers that look wildly out of whack, you

+shouldn't rejoice that you have magically achieved fast

+performance—be skeptical and investigate!

+

+

+> [!TIP]

+> **Defeating let-floating**

+>

+> Fortunately for this particular misbehaving benchmark suite, GHC has

+> an option named

+> [`-fno-full-laziness`](https://downloads.haskell.org/ghc/latest/docs/users_guide/using-optimisation.html#ghc-flag-ffull-laziness)

+> that will turn off let-floating and restore the first two benchmarks

+> to performing in line with the second two.

+>

+> You should not react by simply throwing `-fno-full-laziness` into

+> every GHC-and-criterion command line, as let-floating helps with

+> performance more often than it hurts with benchmarking.

+

+

+## Benchmarking pure functions

+

+Lazy evaluation makes it tricky to benchmark pure code. If we tried to

+saturate a function with all of its arguments and evaluate it

+repeatedly, laziness would ensure that we'd only do “real work” the

+first time through our benchmarking loop. The expression would be

+overwritten with that result, and no further work would happen on

+subsequent loops through our benchmarking harness.

+

+We can defeat laziness by benchmarking an *unsaturated* function—one

+that has been given *all but one* of its arguments.

+

+This is why the

+[`nf`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:nf)

+function accepts two arguments: the first is the almost-saturated

+function we want to benchmark, and the second is the final argument to

+give it.

+

+```haskell

+nf :: NFData b => (a -> b) -> a -> Benchmarkable

+```

+

+As the

+[`NFData`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/deepseq/docs/Control-DeepSeq.html#t:NFData)

+constraint suggests, `nf` applies the argument to the function, then

+evaluates the result to normal form.

+

+The

+[`whnf`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:whnf)

+function evaluates the result of a function only to weak head normal form (WHNF).

+

+```haskell

+whnf :: (a -> b) -> a -> Benchmarkable

+```

+

+If we go back to our first example, we can now fully understand what's

+going on.

+

+```haskell

+main = defaultMain [

+ bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

+ , bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

+ , bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

+ , bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

+ ]

+ ]

+```

+([examples/Fibber.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/Fibber.hs))

+

+We can get away with using `whnf` here because we know that an

+`Int` has only one constructor, so there's no deeper buried

+structure that we'd have to reach using `nf`.

+

+As with benchmarking `IO` actions, there's no clear-cut case for when

+to use `whfn` versus `nf`, especially when a result may be lazily

+generated.

+

+Guidelines for thinking about when to use `nf` or `whnf`:

+

+* If a result is a lazy structure (or a mix of strict and lazy, such

+ as a balanced tree with lazy leaves), how much of it would a

+ real-world caller use? You should be trying to evaluate as much of

+ the result as a realistic consumer would. Blindly using `nf` could

+ cause way too much unnecessary computation.

+

+* If a result is something simple like an `Int`, you're probably safe

+ using `whnf`—but then again, there should be no additional cost to

+ using `nf` in these cases.

+

+

+## Using the criterion command line

+

+By default, a criterion benchmark suite simply runs all of its

+benchmarks. However, criterion accepts a number of arguments to

+control its behaviour. Run your program with `--help` for a complete

+list.

+

+

+### Specifying benchmarks to run

+

+The most common thing you'll want to do is specify which benchmarks

+you want to run. You can do this by simply enumerating each

+benchmark.

+

+```shellsession

+$ ./Fibber 'fib/fib 1'

+```

+

+By default, any names you specify are treated as prefixes to match, so

+you can specify an entire group of benchmarks via a name like

+`"fib/"`. Use the `--match` option to control this behaviour. There are

+currently four ways to configure `--match`:

+

+* `--match prefix`: Check if the given string is a prefix of a benchmark

+ path. For instance, `"foo"` will match `"foobar"`.

+

+* `--match glob`: Use the given string as a Unix-style glob pattern. Bear in

+ mind that performing a glob match on benchmarks names is done as if they were

+ file paths, so for instance both `"*/ba*"` and `"*/*"` will match `"foo/bar"`,

+ but neither `"*"` nor `"*bar"` will match `"foo/bar"`.

+

+* `--match pattern`: Check if the given string is a substring (not necessarily

+ just a prefix) of a benchmark path. For instance `"ooba"` will match

+ `"foobar"`.

+

+* `--match ipattern`: Check if the given string is a substring (not necessarily

+ just a prefix) of a benchmark path, but in a case-insensitive fashion. For

+ instance, `"oObA"` will match `"foobar"`.

+

+### Listing benchmarks

+

+If you've forgotten the names of your benchmarks, run your program

+with `--list` and it will print them all.

+

+

+### How long to spend measuring data

+

+By default, each benchmark runs for 5 seconds.

+

+You can control this using the `--time-limit` option, which specifies

+the minimum number of seconds (decimal fractions are acceptable) that

+a benchmark will spend gathering data. The actual amount of time

+spent may be longer, if more data is needed.

+

+

+### Writing out data

+

+Criterion provides several ways to save data.

+

+The friendliest is as HTML, using `--output`. Files written using

+`--output` are actually generated from Mustache-style templates. The

+only other template provided by default is `json`, so if you run with

+`--template json --output mydata.json`, you'll get a big JSON dump of

+your data.

+

+You can also write out a basic CSV file using `--csv`, a JSON file using

+`--json`, and a JUnit-compatible XML file using `--junit`. (The contents

+of these files are likely to change in the not-too-distant future.)

+

+

+## Linear regression

+

+If you want to perform linear regressions on metrics other than

+elapsed time, use the `--regress` option. This can be tricky to use

+if you are not familiar with linear regression, but here's a thumbnail

+sketch.

+

+The purpose of linear regression is to predict how much one variable

+(the *responder*) will change in response to a change in one or more

+others (the *predictors*).

+

+On each step through a benchmark loop, criterion changes the number of

+iterations. This is the most obvious choice for a predictor

+variable. This variable is named `iters`.

+

+If we want to regress CPU time (`cpuTime`) against iterations, we can

+use `cpuTime:iters` as the argument to `--regress`. This generates

+some additional output on the command line:

+

+```

+time 31.31 ms (30.44 ms .. 32.22 ms)

+ 0.997 R² (0.994 R² .. 0.999 R²)

+mean 30.56 ms (30.01 ms .. 30.99 ms)

+std dev 1.029 ms (754.3 μs .. 1.503 ms)

+

+cpuTime: 0.997 R² (0.994 R² .. 0.999 R²)

+ iters 3.129e-2 (3.039e-2 .. 3.221e-2)

+ y -4.698e-3 (-1.194e-2 .. 1.329e-3)

+```

+

+After the block of normal data, we see a series of new rows.

+

+On the first line of the new block is an R² goodness-of-fit measure,

+so we can see how well our choice of regression fits the data.

+

+On the second line, we get the slope of the `cpuTime`/`iters` curve,

+or (stated another way) how much `cpuTime` each iteration costs.

+

+The last entry is the $y$-axis intercept.

+

+

+### Measuring garbage collector statistics

+

+By default, GHC does not collect statistics about the operation of its

+garbage collector. If you want to measure and regress against GC

+statistics, you must explicitly enable statistics collection at

+runtime using `+RTS -T`.

+

+

+### Useful regressions

+

+| regression | `--regress` | notes

+| -------------------------------|------------------- |-----------

+| CPU cycles | `cycles:iters` |

+| Bytes allocated | `allocated:iters` | `+RTS -T`

+| Number of garbage collections | `numGcs:iters` | `+RTS -T`

+| CPU frequency | `cycles:time` |

+

+

+## Tips, tricks, and pitfalls

+

+While criterion tries hard to automate as much of the benchmarking

+process as possible, there are some things you will want to pay

+attention to.

+

+* Measurements are only as good as the environment in which they're

+ gathered. Try to make sure your computer is quiet when measuring

+ data.

+

+* Be judicious in when you choose `nf` and `whnf`. Always think about

+ what the result of a function is, and how much of it you want to

+ evaluate.

+

+* Simply rerunning a benchmark can lead to variations of a few percent

+ in numbers. This variation can have many causes, including address

+ space layout randomization, recompilation between runs, cache

+ effects, CPU thermal throttling, and the phase of the moon. Don't

+ treat your first measurement as golden!

+

+* Keep an eye out for completely bogus numbers, as in the case of

+ `-fno-full-laziness` above.

+

+* When you need trustworthy results from a benchmark suite, run each

+ measurement as a separate invocation of your program. When you run

+ a number of benchmarks during a single program invocation, you will

+ sometimes see them interfere with each other.

+

+

+### How to sniff out bogus results

+

+If some external factors are making your measurements noisy, criterion

+tries to make it easy to tell. At the level of raw data, noisy

+measurements will show up as “outliers”, but you shouldn't need to

+inspect the raw data directly.

+

+The easiest yellow flag to spot is the R² goodness-of-fit measure

+dropping below 0.9. If this happens, scrutinise your data carefully.

+

+Another easy pattern to look for is severe outliers in the raw

+measurement chart when you're using `--output`. These should be easy

+to spot: they'll be points sitting far from the linear regression line

+(usually above it).

+

+If the lower and upper bounds on an estimate aren't “tight” (close to

+the estimate), this suggests that noise might be having some kind of

+negative effect.

-Master [github repository](https://github.com/haskell/criterion):

+A warning about “variance introduced by outliers” may be printed.

+This indicates the degree to which the standard deviation is inflated

+by outlying measurements, as in the following snippet (notice that the

+lower and upper bounds aren't all that tight, too).

-* `git clone https://github.com/haskell/criterion.git`

+```

+std dev 652.0 ps (507.7 ps .. 942.1 ps)

+variance introduced by outliers: 91% (severely inflated)

+```

-# Authors

+## Generating (HTML) reports from previous benchmarks with criterion-report

-This library is written and maintained by Bryan O'Sullivan,

-

+

+

+### Understanding charts

+

+A report begins with a summary of all the numbers measured.

+Underneath is a breakdown of every benchmark, each with two charts and

+some explanation.

+

+The chart on the left is a

+[kernel density estimate](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kernel_density_estimation)

+(also known as a KDE) of time measurements. This graphs the

+*probability* of any given time measurement occurring. A spike

+indicates that a measurement of a particular time occurred; its height

+indicates how often that measurement was repeated.

+

+> [!NOTE]

+> **Why not use a histogram?**

+>

+> A more popular alternative to the KDE for this kind of display is the

+> [histogram](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histogram). Why do we use a

+> KDE instead? In order to get good information out of a histogram, you

+> have to

+> [choose a suitable bin size](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histogram#Number_of_bins_and_width).

+> This is a fiddly manual task. In contrast, a KDE is likely to be

+> informative immediately, with no configuration required.

+

+The chart on the right contains the raw measurements from which the

+kernel density estimate was built. The $x$ axis indicates the number

+of loop iterations, while the $y$ axis shows measured execution time

+for the given number of iterations. The line “behind” the values is a

+linear regression generated from this data. Ideally, all measurements

+will be on (or very near) this line.

+

+

+### Understanding the data under a chart

+

+Underneath the chart for each benchmark is a small table of

+information that looks like this.

+

+| | lower bound | estimate | upper bound |

+|----------------------|-------------|------------|-------------|

+| OLS regression | 31.0 ms | 37.4 ms | 42.9 ms |

+| R² goodness-of-fit | 0.887 | 0.942 | 0.994 |

+| Mean execution time | 34.8 ms | 37.0 ms | 43.1 ms |

+| Standard deviation | 2.11 ms | 6.49 ms | 11.0 ms |

+

+The second row is the result of a linear regression run on the measurements displayed in the right-hand chart.

+

+* “**OLS regression**” estimates the time needed for a single

+ execution of the activity being benchmarked, using an

+ [ordinary least-squares regression model](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ordinary_least_squares).

+ This number should be similar to the “mean execution time” row a

+ couple of rows beneath. The OLS estimate is usually more accurate

+ than the mean, as it more effectively eliminates measurement

+ overhead and other constant factors.

+

+* “**R² goodness-of-fit**” is a measure of how accurately the linear

+ regression model fits the observed measurements. If the measurements

+ are not too noisy, R² should lie between 0.99 and 1, indicating an

+ excellent fit. If the number is below 0.99, something is confounding

+ the accuracy of the linear model. A value below 0.9 is outright

+ worrisome.

+

+* “**Mean execution time**” and “**Standard deviation**” are

+ statistics calculated (more or less) from execution time divided by

+ number of iterations.

+

+On either side of the main column of values are greyed-out lower and

+upper bounds. These measure the *accuracy* of the main estimate using

+a statistical technique called

+[*bootstrapping*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bootstrapping_(statistics)). This

+tells us that when randomly resampling the data, 95% of estimates fell

+within between the lower and upper bounds. When the main estimate is

+of good quality, the lower and upper bounds will be close to its

+value.

+

+

+## Reading command line output

+

+Before you look at HTML reports, you'll probably start by inspecting

+the report that criterion prints in your terminal window.

+

+```

+benchmarking ByteString/HashMap/random

+time 4.046 ms (4.020 ms .. 4.072 ms)

+ 1.000 R² (1.000 R² .. 1.000 R²)

+mean 4.017 ms (4.010 ms .. 4.027 ms)

+std dev 27.12 μs (20.45 μs .. 38.17 μs)

+```

+

+The first column is a name; the second is an estimate. The third and

+fourth, in parentheses, are the 95% lower and upper bounds on the

+estimate.

+

+* `time` corresponds to the “OLS regression” field in the HTML table

+ above.

+

+* `R²` is the goodness-of-fit metric for `time`.

+

+* `mean` and `std dev` have the same meanings as “Mean execution time”

+ and “Standard deviation” in the HTML table.

+

+

+## How to write a benchmark suite

+

+A criterion benchmark suite consists of a series of

+[`Benchmark`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#t:Benchmark)

+values.

+

+```haskell

+main = defaultMain [

+ bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

+ , bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

+ , bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

+ , bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

+ ]

+ ]

+```

+

+

+We group related benchmarks together using the

+[`bgroup`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:bgroup)

+function. Its first argument is a name for the group of benchmarks.

+

+```haskell

+bgroup :: String -> [Benchmark] -> Benchmark

+```

+

+All the magic happens with the

+[`bench`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:bench)

+function. The first argument to `bench` is a name that describes the

+activity we're benchmarking.

+

+```haskell

+bench :: String -> Benchmarkable -> Benchmark

+bench = Benchmark

+```

+

+The

+[`Benchmarkable`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#t:Benchmarkable)

+type is a container for code that can be benchmarked.

+

+By default, criterion allows two kinds of code to be benchmarked.

+

+* Any `IO` action can be benchmarked directly.

+

+* With a little trickery, we can benchmark pure functions.

+

+

+### Benchmarking an `IO` action

+

+This function shows how we can benchmark an `IO` action.

+

+```haskell

+import Criterion.Main

+

+main = defaultMain [

+ bench "readFile" $ nfIO (readFile "GoodReadFile.hs")

+ ]

+```

+([examples/GoodReadFile.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/GoodReadFile.hs))

+

+We use

+[`nfIO`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:nfIO)

+to specify that after we run the `IO` action, its result must be

+evaluated to normal form, i.e. so that

+all of its internal constructors are fully evaluated, and it contains

+no thunks.

+

+```haskell

+nfIO :: NFData a => IO a -> Benchmarkable

+```

+

+Rules of thumb for when to use `nfIO`:

+

+* Any time that lazy I/O is involved, use `nfIO` to avoid resource

+ leaks.

+

+* If you're not sure how much evaluation will have been performed on

+ the result of an action, use `nfIO` to be certain that it's fully

+ evaluated.

+

+

+### `IO` and `seq`

+

+In addition to `nfIO`, criterion provides a

+[`whnfIO`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:whnfIO)

+function that evaluates the result of an action only deep enough for

+the outermost constructor to be known (using `seq`). This is known as

+**weak head normal form** (WHNF).

+

+```haskell

+whnfIO :: IO a -> Benchmarkable

+```

+

+This function is useful if your `IO` action returns a simple value

+like an `Int`, or something more complex like a

+[`Map`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/containers/docs/Data-Map-Lazy.html#t:Map)

+where evaluating the outermost constructor will do “enough work”.

+

+

+## Be careful with lazy I/O!

+

+Experienced Haskell programmers don't use lazy I/O very often, and

+here's an example of why: if you try to run the benchmark below, it

+will probably *crash*.

+

+```haskell

+import Criterion.Main

+

+main = defaultMain [

+ bench "whnfIO readFile" $ whnfIO (readFile "BadReadFile.hs")

+ ]

+```

+([examples/BadReadFile.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/BadReadFile.hs))

+

+The reason for the crash is that `readFile` reads the contents of a

+file lazily: it can't close the file handle until whoever opened the

+file reads the whole thing. Since `whnfIO` only evaluates the very

+first constructor after the file is opened, the benchmarking loop

+causes a large number of open files to accumulate, until the

+inevitable occurs:

+

+```shellsession

+$ ./BadReadFile

+benchmarking whnfIO readFile

+openFile: resource exhausted (Too many open files)

+```

+

+

+## Beware “pretend” I/O!

+

+GHC is an aggressive compiler. If you have an `IO` action that

+doesn't really interact with the outside world, *and* it has just the

+right structure, GHC may notice that a substantial amount of its

+computation can be memoised via “let-floating”.

+

+There exists a

+[somewhat contrived example](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/ConduitVsPipes.hs)

+of this problem, where the first two benchmarks run between 40 and

+40,000 times faster than they “should”.

+

+As always, if you see numbers that look wildly out of whack, you

+shouldn't rejoice that you have magically achieved fast

+performance—be skeptical and investigate!

+

+

+> [!TIP]

+> **Defeating let-floating**

+>

+> Fortunately for this particular misbehaving benchmark suite, GHC has

+> an option named

+> [`-fno-full-laziness`](https://downloads.haskell.org/ghc/latest/docs/users_guide/using-optimisation.html#ghc-flag-ffull-laziness)

+> that will turn off let-floating and restore the first two benchmarks

+> to performing in line with the second two.

+>

+> You should not react by simply throwing `-fno-full-laziness` into

+> every GHC-and-criterion command line, as let-floating helps with

+> performance more often than it hurts with benchmarking.

+

+

+## Benchmarking pure functions

+

+Lazy evaluation makes it tricky to benchmark pure code. If we tried to

+saturate a function with all of its arguments and evaluate it

+repeatedly, laziness would ensure that we'd only do “real work” the

+first time through our benchmarking loop. The expression would be

+overwritten with that result, and no further work would happen on

+subsequent loops through our benchmarking harness.

+

+We can defeat laziness by benchmarking an *unsaturated* function—one

+that has been given *all but one* of its arguments.

+

+This is why the

+[`nf`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:nf)

+function accepts two arguments: the first is the almost-saturated

+function we want to benchmark, and the second is the final argument to

+give it.

+

+```haskell

+nf :: NFData b => (a -> b) -> a -> Benchmarkable

+```

+

+As the

+[`NFData`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/deepseq/docs/Control-DeepSeq.html#t:NFData)

+constraint suggests, `nf` applies the argument to the function, then

+evaluates the result to normal form.

+

+The

+[`whnf`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:whnf)

+function evaluates the result of a function only to weak head normal form (WHNF).

+

+```haskell

+whnf :: (a -> b) -> a -> Benchmarkable

+```

+

+If we go back to our first example, we can now fully understand what's

+going on.

+

+```haskell

+main = defaultMain [

+ bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

+ , bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

+ , bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

+ , bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

+ ]

+ ]

+```

+([examples/Fibber.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/Fibber.hs))

+

+We can get away with using `whnf` here because we know that an

+`Int` has only one constructor, so there's no deeper buried

+structure that we'd have to reach using `nf`.

+

+As with benchmarking `IO` actions, there's no clear-cut case for when

+to use `whfn` versus `nf`, especially when a result may be lazily

+generated.

+

+Guidelines for thinking about when to use `nf` or `whnf`:

+

+* If a result is a lazy structure (or a mix of strict and lazy, such

+ as a balanced tree with lazy leaves), how much of it would a

+ real-world caller use? You should be trying to evaluate as much of

+ the result as a realistic consumer would. Blindly using `nf` could

+ cause way too much unnecessary computation.

+

+* If a result is something simple like an `Int`, you're probably safe

+ using `whnf`—but then again, there should be no additional cost to

+ using `nf` in these cases.

+

+

+## Using the criterion command line

+

+By default, a criterion benchmark suite simply runs all of its

+benchmarks. However, criterion accepts a number of arguments to

+control its behaviour. Run your program with `--help` for a complete

+list.

+

+

+### Specifying benchmarks to run

+

+The most common thing you'll want to do is specify which benchmarks

+you want to run. You can do this by simply enumerating each

+benchmark.

+

+```shellsession

+$ ./Fibber 'fib/fib 1'

+```

+

+By default, any names you specify are treated as prefixes to match, so

+you can specify an entire group of benchmarks via a name like

+`"fib/"`. Use the `--match` option to control this behaviour. There are

+currently four ways to configure `--match`:

+

+* `--match prefix`: Check if the given string is a prefix of a benchmark

+ path. For instance, `"foo"` will match `"foobar"`.

+

+* `--match glob`: Use the given string as a Unix-style glob pattern. Bear in

+ mind that performing a glob match on benchmarks names is done as if they were

+ file paths, so for instance both `"*/ba*"` and `"*/*"` will match `"foo/bar"`,

+ but neither `"*"` nor `"*bar"` will match `"foo/bar"`.

+

+* `--match pattern`: Check if the given string is a substring (not necessarily

+ just a prefix) of a benchmark path. For instance `"ooba"` will match

+ `"foobar"`.

+

+* `--match ipattern`: Check if the given string is a substring (not necessarily

+ just a prefix) of a benchmark path, but in a case-insensitive fashion. For

+ instance, `"oObA"` will match `"foobar"`.

+

+### Listing benchmarks

+

+If you've forgotten the names of your benchmarks, run your program

+with `--list` and it will print them all.

+

+

+### How long to spend measuring data

+

+By default, each benchmark runs for 5 seconds.

+

+You can control this using the `--time-limit` option, which specifies

+the minimum number of seconds (decimal fractions are acceptable) that

+a benchmark will spend gathering data. The actual amount of time

+spent may be longer, if more data is needed.

+

+

+### Writing out data

+

+Criterion provides several ways to save data.

+

+The friendliest is as HTML, using `--output`. Files written using

+`--output` are actually generated from Mustache-style templates. The

+only other template provided by default is `json`, so if you run with

+`--template json --output mydata.json`, you'll get a big JSON dump of

+your data.

+

+You can also write out a basic CSV file using `--csv`, a JSON file using

+`--json`, and a JUnit-compatible XML file using `--junit`. (The contents

+of these files are likely to change in the not-too-distant future.)

+

+

+## Linear regression

+

+If you want to perform linear regressions on metrics other than

+elapsed time, use the `--regress` option. This can be tricky to use

+if you are not familiar with linear regression, but here's a thumbnail

+sketch.

+

+The purpose of linear regression is to predict how much one variable

+(the *responder*) will change in response to a change in one or more

+others (the *predictors*).

+

+On each step through a benchmark loop, criterion changes the number of

+iterations. This is the most obvious choice for a predictor

+variable. This variable is named `iters`.

+

+If we want to regress CPU time (`cpuTime`) against iterations, we can

+use `cpuTime:iters` as the argument to `--regress`. This generates

+some additional output on the command line:

+

+```

+time 31.31 ms (30.44 ms .. 32.22 ms)

+ 0.997 R² (0.994 R² .. 0.999 R²)

+mean 30.56 ms (30.01 ms .. 30.99 ms)

+std dev 1.029 ms (754.3 μs .. 1.503 ms)

+

+cpuTime: 0.997 R² (0.994 R² .. 0.999 R²)

+ iters 3.129e-2 (3.039e-2 .. 3.221e-2)

+ y -4.698e-3 (-1.194e-2 .. 1.329e-3)

+```

+

+After the block of normal data, we see a series of new rows.

+

+On the first line of the new block is an R² goodness-of-fit measure,

+so we can see how well our choice of regression fits the data.

+

+On the second line, we get the slope of the `cpuTime`/`iters` curve,

+or (stated another way) how much `cpuTime` each iteration costs.

+

+The last entry is the $y$-axis intercept.

+

+

+### Measuring garbage collector statistics

+

+By default, GHC does not collect statistics about the operation of its

+garbage collector. If you want to measure and regress against GC

+statistics, you must explicitly enable statistics collection at

+runtime using `+RTS -T`.

+

+

+### Useful regressions

+

+| regression | `--regress` | notes

+| -------------------------------|------------------- |-----------

+| CPU cycles | `cycles:iters` |

+| Bytes allocated | `allocated:iters` | `+RTS -T`

+| Number of garbage collections | `numGcs:iters` | `+RTS -T`

+| CPU frequency | `cycles:time` |

+

+

+## Tips, tricks, and pitfalls

+

+While criterion tries hard to automate as much of the benchmarking

+process as possible, there are some things you will want to pay

+attention to.

+

+* Measurements are only as good as the environment in which they're

+ gathered. Try to make sure your computer is quiet when measuring

+ data.

+

+* Be judicious in when you choose `nf` and `whnf`. Always think about

+ what the result of a function is, and how much of it you want to

+ evaluate.

+

+* Simply rerunning a benchmark can lead to variations of a few percent

+ in numbers. This variation can have many causes, including address

+ space layout randomization, recompilation between runs, cache

+ effects, CPU thermal throttling, and the phase of the moon. Don't

+ treat your first measurement as golden!

+

+* Keep an eye out for completely bogus numbers, as in the case of

+ `-fno-full-laziness` above.

+

+* When you need trustworthy results from a benchmark suite, run each

+ measurement as a separate invocation of your program. When you run

+ a number of benchmarks during a single program invocation, you will

+ sometimes see them interfere with each other.

+

+

+### How to sniff out bogus results

+

+If some external factors are making your measurements noisy, criterion

+tries to make it easy to tell. At the level of raw data, noisy

+measurements will show up as “outliers”, but you shouldn't need to

+inspect the raw data directly.

+

+The easiest yellow flag to spot is the R² goodness-of-fit measure

+dropping below 0.9. If this happens, scrutinise your data carefully.

+

+Another easy pattern to look for is severe outliers in the raw

+measurement chart when you're using `--output`. These should be easy

+to spot: they'll be points sitting far from the linear regression line

+(usually above it).

+

+If the lower and upper bounds on an estimate aren't “tight” (close to

+the estimate), this suggests that noise might be having some kind of

+negative effect.

-Master [github repository](https://github.com/haskell/criterion):

+A warning about “variance introduced by outliers” may be printed.

+This indicates the degree to which the standard deviation is inflated

+by outlying measurements, as in the following snippet (notice that the

+lower and upper bounds aren't all that tight, too).

-* `git clone https://github.com/haskell/criterion.git`

+```

+std dev 652.0 ps (507.7 ps .. 942.1 ps)

+variance introduced by outliers: 91% (severely inflated)

+```

-# Authors

+## Generating (HTML) reports from previous benchmarks with criterion-report

-This library is written and maintained by Bryan O'Sullivan,

- -

-

-# Features

-

-* The simple API hides a lot of automation and details that you

- shouldn't need to worry about.

-

-* Sophisticated, high-resolution analysis can accurately measure

- operations that run in as little as a few hundred picoseconds.

-

-* [Output to active HTML](report.html) (with Javascript charts), CSV,

- and JSON. Write your own report templates to customize exactly how

- your results are presented.

-

-* Linear regression model allows measurement of the effects of garbage

- collection and other factors.

-

-* Measurements are cross-validated to ensure that sources of

- significant noise (usually other activity on the system) can be

- identified.

-

-

-# A complete example

-

-This is a complete program that defines a group of three benchmarks.

-

-~~~~ {.haskell}

-import Criterion.Main

-

--- The function we're benchmarking.

-fib :: Int -> Int

-fib m | m < 0 = error "negative!"

- | otherwise = go m

- where

- go 0 = 0

- go 1 = 1

- go n = go (n-1) + go (n-2)

-

-main :: IO ()

-main = defaultMain [

- bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

- , bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

- , bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

- , bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

- ]

- ]

-~~~~

-([examples/Fibber.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/Fibber.hs))

-

-

-

-

-

-# Features

-

-* The simple API hides a lot of automation and details that you

- shouldn't need to worry about.

-

-* Sophisticated, high-resolution analysis can accurately measure

- operations that run in as little as a few hundred picoseconds.

-

-* [Output to active HTML](report.html) (with Javascript charts), CSV,

- and JSON. Write your own report templates to customize exactly how

- your results are presented.

-

-* Linear regression model allows measurement of the effects of garbage

- collection and other factors.

-

-* Measurements are cross-validated to ensure that sources of

- significant noise (usually other activity on the system) can be

- identified.

-

-

-# A complete example

-

-This is a complete program that defines a group of three benchmarks.

-

-~~~~ {.haskell}

-import Criterion.Main

-

--- The function we're benchmarking.

-fib :: Int -> Int

-fib m | m < 0 = error "negative!"

- | otherwise = go m

- where

- go 0 = 0

- go 1 = 1

- go n = go (n-1) + go (n-2)

-

-main :: IO ()

-main = defaultMain [

- bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

- , bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

- , bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

- , bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

- ]

- ]

-~~~~

-([examples/Fibber.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/Fibber.hs))

-

-

-

-

diff --git a/www/template.html b/www/template.html

deleted file mode 100644

index 45fb977..0000000

--- a/www/template.html

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,96 +0,0 @@

-

-

-

-

-

-

-$for(author-meta)$

-

-$endfor$

-$if(date-meta)$

-

-$endif$

-

-

- Ready to jump in?

- -I've worked hard to make `criterion` easy to learn, so that you can -write dependable, accurate benchmarks without having to become a -benchmarking expert. - -Tutorial - -I'm proud of the example-filled docs. - -Documentation - -If you run into problems, let me know. - -Issues - -

-

-

- $endif$

-

-

-

-

- $title$

- $for(author)$ -$author$

- $endfor$ -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

diff --git a/www/tutorial.md b/www/tutorial.md

deleted file mode 100644

index 74be1d7..0000000

--- a/www/tutorial.md

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,667 +0,0 @@

-% A criterion tutorial

-% Learn how to write Haskell microbenchmarks.

-

-# Getting started

-

-Here's `Fibber.hs`: a simple and complete benchmark, measuring the performance of

-the ever-ridiculous `fib` function.

-

-~~~~ {.haskell}

-{- cabal:

-build-depends: base, criterion

--}

-

-import Criterion.Main

-

--- The function we're benchmarking.

-fib :: Int -> Int

-fib m | m < 0 = error "negative!"

- | otherwise = go m

- where

- go 0 = 0

- go 1 = 1

- go n = go (n - 1) + go (n - 2)

-

--- Our benchmark harness.

-main = defaultMain [

- bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

- , bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

- , bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

- , bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

- ]

- ]

-~~~~

-([examples/Fibber.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/Fibber.hs))

-

-The

-[`defaultMain`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:defaultMain)

-function takes a list of

-[`Benchmark`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#t:Benchmark)

-values, each of which describes a function to benchmark. (We'll come

-back to `bench` and `whnf` shortly, don't worry.)

-

-To maximise our convenience, `defaultMain` will parse command line

-arguments and then run any benchmarks we ask. Let's run our benchmark

-program (it might take some time if you never used Criterion before, since

-the library has to be downloaded and compiled).

-

-~~~~

-$ cabal run Fibber.hs

-benchmarking fib/1

-time 13.77 ns (13.49 ns .. 14.07 ns)

- 0.998 R² (0.997 R² .. 1.000 R²)

-mean 13.56 ns (13.49 ns .. 13.70 ns)

-std dev 305.1 ps (64.14 ps .. 532.5 ps)

-variance introduced by outliers: 36% (moderately inflated)

-

-benchmarking fib/5

-time 173.9 ns (172.8 ns .. 175.6 ns)

- 1.000 R² (0.999 R² .. 1.000 R²)

-mean 173.8 ns (173.1 ns .. 175.4 ns)

-std dev 3.149 ns (1.842 ns .. 5.954 ns)

-variance introduced by outliers: 23% (moderately inflated)

-

-benchmarking fib/9

-time 1.219 μs (1.214 μs .. 1.228 μs)

- 1.000 R² (1.000 R² .. 1.000 R²)

-mean 1.219 μs (1.216 μs .. 1.223 μs)

-std dev 12.43 ns (9.907 ns .. 17.29 ns)

-

-benchmarking fib/11

-time 3.253 μs (3.246 μs .. 3.260 μs)

- 1.000 R² (1.000 R² .. 1.000 R²)

-mean 3.248 μs (3.243 μs .. 3.254 μs)

-std dev 18.94 ns (16.57 ns .. 21.95 ns)

-

-~~~~

-

-Even better, the `--output` option directs our program to write a

-report to the file [`fibber.html`](fibber.html).

-

-~~~~

-$ cabal run Fibber.hs -- --output fibber.html

-...similar output as before...

-~~~~

-

-Click on the image to see a complete report. If you mouse over the data

-points in the charts, you'll see that they are *live*, giving additional

-information about what's being displayed.

-

-

-

-

- $for(include-before)$

- $include-before$

- $endfor$

- $body$

- $for(include-after)$

- $include-after$

- $endfor$

-

- $if(toc)$

-

-

-

- $endif$

-  -

-

-# Understanding charts

-

-A report begins with a summary of all the numbers measured.

-Underneath is a breakdown of every benchmark, each with two charts and

-some explanation.

-

-The chart on the left is a

-[kernel density estimate](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kernel_density_estimation)

-(also known as a KDE) of time measurements. This graphs the

-*probability* of any given time measurement occurring. A spike

-indicates that a measurement of a particular time occurred; its height

-indicates how often that measurement was repeated.

-

-

-

-

-# Understanding charts

-

-A report begins with a summary of all the numbers measured.

-Underneath is a breakdown of every benchmark, each with two charts and

-some explanation.

-

-The chart on the left is a

-[kernel density estimate](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kernel_density_estimation)

-(also known as a KDE) of time measurements. This graphs the

-*probability* of any given time measurement occurring. A spike

-indicates that a measurement of a particular time occurred; its height

-indicates how often that measurement was repeated.

-

-

-#### Why not use a histogram?

-

-A more popular alternative to the KDE for this kind of display is the

-[histogram](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histogram). Why do we use a

-KDE instead? In order to get good information out of a histogram, you

-have to

-[choose a suitable bin size](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histogram#Number_of_bins_and_width).

-This is a fiddly manual task. In contrast, a KDE is likely to be

-informative immediately, with no configuration required.

-

-

-The chart on the right contains the raw measurements from which the

-kernel density estimate was built. The $x$ axis indicates the number

-of loop iterations, while the $y$ axis shows measured execution time

-for the given number of iterations. The line "behind" the values is a

-linear regression generated from this data. Ideally, all measurements

-will be on (or very near) this line.

-

-

-## Understanding the data under a chart

-

-Underneath the chart for each benchmark is a small table of

-information that looks like this.

-

-| - | lower bound | -estimate | -upper bound | -

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS regression | -31.0 ms | -37.4 ms | -42.9 ms | -

| R² goodness-of-fit | -0.887 | -0.942 | -0.994 | -

| Mean execution time | -34.8 ms | -37.0 ms | -43.1 ms | -

| Standard deviation | -2.11 ms | -6.49 ms | -11.0 ms | -

-#### Defeating let-floating

-

-Fortunately for this particular misbehaving benchmark suite, GHC has

-an option named

-[`-fno-full-laziness`](https://www.haskell.org/ghc/docs/latest/html/users_guide/options-optimise.html)

-that will turn off let-floating and restore the first two benchmarks

-to performing in line with the second two.

-

-You should not react by simply throwing `-fno-full-laziness` into

-every GHC-and-criterion command line, as let-floating helps with

-performance more often than it hurts with benchmarking.

-

-

-

-# Benchmarking pure functions

-

-Lazy evaluation makes it tricky to benchmark pure code. If we tried to

-saturate a function with all of its arguments and evaluate it

-repeatedly, laziness would ensure that we'd only do "real work" the

-first time through our benchmarking loop. The expression would be

-overwritten with that result, and no further work would happen on

-subsequent loops through our benchmarking harness.

-

-We can defeat laziness by benchmarking an *unsaturated* function---one

-that has been given *all but one* of its arguments.

-

-This is why the

-[`nf`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:nf)

-function accepts two arguments: the first is the almost-saturated

-function we want to benchmark, and the second is the final argument to

-give it.

-

-~~~~ {.haskell}

-nf :: NFData b => (a -> b) -> a -> Benchmarkable

-~~~~

-

-As the

-[`NFData`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/deepseq/docs/Control-DeepSeq.html#t:NFData)

-constraint suggests, `nf` applies the argument to the function, then

-evaluates the result to normal form.

-

-The

-[`whnf`](http://hackage.haskell.org/package/criterion/docs/Criterion-Main.html#v:whnf)

-function evaluates the result of a function only to weak head normal form (WHNF).

-

-~~~~ {.haskell}

-whnf :: (a -> b) -> a -> Benchmarkable

-~~~~

-

-If we go back to our first example, we can now fully understand what's

-going on.

-

-~~~~ {.haskell}

-main = defaultMain [

- bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

- , bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

- , bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

- , bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

- ]

- ]

-~~~~

-([examples/Fibber.hs](https://github.com/haskell/criterion/blob/master/examples/Fibber.hs))

-

-We can get away with using `whnf` here because we know that an

-`Int` has only one constructor, so there's no deeper buried

-structure that we'd have to reach using `nf`.

-

-As with benchmarking `IO` actions, there's no clear-cut case for when

-to use `whfn` versus `nf`, especially when a result may be lazily

-generated.

-

-Guidelines for thinking about when to use `nf` or `whnf`:

-

-* If a result is a lazy structure (or a mix of strict and lazy, such

- as a balanced tree with lazy leaves), how much of it would a

- real-world caller use? You should be trying to evaluate as much of

- the result as a realistic consumer would. Blindly using `nf` could

- cause way too much unnecessary computation.

-

-* If a result is something simple like an `Int`, you're probably safe

- using `whnf`---but then again, there should be no additional cost to

- using `nf` in these cases.

-

-

-# Using the criterion command line

-

-By default, a criterion benchmark suite simply runs all of its

-benchmarks. However, criterion accepts a number of arguments to

-control its behaviour. Run your program with `--help` for a complete

-list.

-

-

-## Specifying benchmarks to run

-

-The most common thing you'll want to do is specify which benchmarks

-you want to run. You can do this by simply enumerating each

-benchmark.

-

-~~~~ {.haskell}

-./Fibber 'fib/fib 1'

-~~~~

-

-By default, any names you specify are treated as prefixes to match, so

-you can specify an entire group of benchmarks via a name like

-`"fib/"`. Use the `--match` option to control this behaviour. There are

-currently four ways to configure `--match`:

-

-* `--match prefix`: Check if the given string is a prefix of a benchmark

- path. For instance, `"foo"` will match `"foobar"`.

-

-* `--match glob`: Use the given string as a Unix-style glob pattern. Bear in

- mind that performing a glob match on benchmarks names is done as if they were

- file paths, so for instance both `"*/ba*"` and `"*/*"` will match `"foo/bar"`,

- but neither `"*"` nor `"*bar"` will match `"foo/bar"`.

-

-* `--match pattern`: Check if the given string is a substring (not necessarily

- just a prefix) of a benchmark path. For instance `"ooba"` will match

- `"foobar"`.

-

-* `--match ipattern`: Check if the given string is a substring (not necessarily

- just a prefix) of a benchmark path, but in a case-insensitive fashion. For

- instance, `"oObA"` will match `"foobar"`.

-

-## Listing benchmarks

-

-If you've forgotten the names of your benchmarks, run your program

-with `--list` and it will print them all.

-

-

-## How long to spend measuring data

-

-By default, each benchmark runs for 5 seconds.

-

-You can control this using the `--time-limit` option, which specifies

-the minimum number of seconds (decimal fractions are acceptable) that

-a benchmark will spend gathering data. The actual amount of time

-spent may be longer, if more data is needed.

-

-

-## Writing out data

-

-Criterion provides several ways to save data.

-

-The friendliest is as HTML, using `--output`. Files written using

-`--output` are actually generated from Mustache-style templates. The

-only other template provided by default is `json`, so if you run with

-`--template json --output mydata.json`, you'll get a big JSON dump of

-your data.

-

-You can also write out a basic CSV file using `--csv`, a JSON file using

-`--json`, and a JUnit-compatible XML file using `--junit`. (The contents

-of these files are likely to change in the not-too-distant future.)

-

-

-# Linear regression

-

-If you want to perform linear regressions on metrics other than

-elapsed time, use the `--regress` option. This can be tricky to use

-if you are not familiar with linear regression, but here's a thumbnail

-sketch.

-

-The purpose of linear regression is to predict how much one variable

-(the *responder*) will change in response to a change in one or more

-others (the *predictors*).

-

-On each step through through a benchmark loop, criterion changes the number of

-iterations. This is the most obvious choice for a predictor

-variable. This variable is named `iters`.

-

-If we want to regress CPU time (`cpuTime`) against iterations, we can

-use `cpuTime:iters` as the argument to `--regress`. This generates

-some additional output on the command line:

-

-~~~~

-time 31.31 ms (30.44 ms .. 32.22 ms)

- 0.997 R² (0.994 R² .. 0.999 R²)

-mean 30.56 ms (30.01 ms .. 30.99 ms)

-std dev 1.029 ms (754.3 μs .. 1.503 ms)

-

-cpuTime: 0.997 R² (0.994 R² .. 0.999 R²)

- iters 3.129e-2 (3.039e-2 .. 3.221e-2)

- y -4.698e-3 (-1.194e-2 .. 1.329e-3)

-~~~~

-

-After the block of normal data, we see a series of new rows.

-

-On the first line of the new block is an R² goodness-of-fit measure,

-so we can see how well our choice of regression fits the data.

-

-On the second line, we get the slope of the `cpuTime`/`iters` curve,

-or (stated another way) how much `cpuTime` each iteration costs.

-

-The last entry is the $y$-axis intercept.

-

-

-## Measuring garbage collector statistics

-

-By default, GHC does not collect statistics about the operation of its

-garbage collector. If you want to measure and regress against GC

-statistics, you must explicitly enable statistics collection at

-runtime using `+RTS -T`.

-

-

-## Useful regressions

-

-| regression | -`--regress` | -notes | -

|---|---|---|

| CPU cycles | -`cycles:iters` | -- |

| Bytes allocated | -`allocated:iters` | -`+RTS -T` | -

| Number of garbage collections | -`numGcs:iters` | -`+RTS -T` | -

| CPU frequency | -`cycles:time` | -- |

+

+